Finance for mathematicians (part II)

This post is something of a sequel to a post from two years ago where I used commutative diagrams to understand finance. A few people wanted me to write a follow-up and I dragged my feet for a long time. Then it randomly appeared on Reddit, and then my ego kicked in, and I always listen to my ego now days because I’m tired of being controlled by the Buddha.

backstory

Three hundred years ago, Thomas Newcomen invented an early version of the steam engine using the Rankine cycle. This notion of exploiting something while returning to where you started to exploit again was generalized by Carnot who jotted down his ideas for exploiting the relationship between pressure, volume, temperature, and entropy to literally move mountains. The carnot cycle is representing in psuedo-code as:

Light a furnace

while True:

trade pressure for volume

Extract work during a cooling phase

Trade volume for pressure (at constant temperature)

Heat things up again from your furnace

This loop is diagramed on wikipedia like this

Then steam powered locomotives, sewing machines, children working in factories, machine guns, the internal combustion engine, World War I, assembly lines, World War II, Bikini Atoll, Hiroshima, USSR, the transistor, soda fountains, television, betamax, the Apple II, and then I was sitting in a class on biomechanics and the teacher (Michael Dickenson), drew this diagram like this on the white-board

The diagram explains the extraction of work from a muscle. This could not be a coincidence, it was a conspiracy.

They control everything and they can be anywhere

The airlines are also involved. Lift in irrotational flows is derived by integrating over a loop1. At this point it was no surprise that my advisors at Caltech, Mathieu Desbrun and Jerry Marsden were in on it too. The evidence of this can be seen in their (seemingly innocuous) work on computer graphics. That’s just a cover, this goes deep.

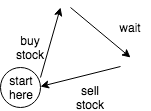

They are all in on it. The industrialists, the Russian, and even the suits on wall street. Years later, I jotted down this commutative diagram to understand stock trading.

The top arrow represents the interest rate on a loan. The p’s refer to trading dollars for shares of stock, and so \(p^{-1}\) refers to the process of selling a share of stock. If there is an arbitrage opportunity, then this diagram does not commute. You can take out a loan, buy a stock, wait, and then sell the stock. This the map \(p_{\operatorname{future}^{-1}} \circ \operatorname{wait} \circ p\). It’s an arbitrage in your favor if the return on investment is greater than the interest rate of the loan, \(r\).

Diagramatically, capturing arbitrage involves traversing this triangle

If you take the dual diagram, and find/replace dollars/present shares of stock/future shares with slaves/sugar/rum you get the original triangle trade. The ubiquity of this phenomena is eerie until you go down the rabbit hole and find the common culprit.

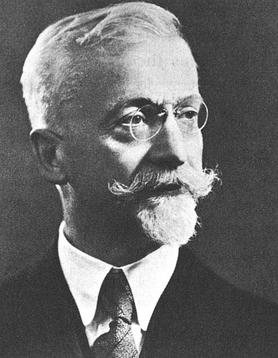

The puppet master

It’s unclear who to target, but Elie Cartan certainly had the final word. All these phenomena involve the calculation of the area on the interior of a bounded region to a line integral over a boundary, which can be seen as a special case of the Stokes theorem. Elie Cartan is credited with inventing exterior calculus, and discovering the modern characterization of Stokes theorem.

Stokes theorem and the exterior derivative

Recall, given any differential form \(\omega\), the integral of \(\omega\) over the boundary of some region \(\partial \Omega\) is given by \begin{align} \int_{\partial \Omega} \omega = \int_\Omega d\omega. \end{align} In fact this theorem can be used as an alternative definition of the exterior derivative. That is, we can define \(d \omega\) as the unique \({k+1}\)-form, such that Stokes theorem hold for arbitrary \(k\)-submanifolds with boundary. Such a definition would be consistent with defining \(k\)-forms as

Alternative Definition of \(k\)-form: A \(k\)-form, \(\alpha\), is a map from oriented2 \(k\)-submanifolds of \(M\) to the reals, such that \(\alpha(N_1 \uplus N_2) = \alpha(N_1) + \alpha(N_2)\), where \(\uplus\) denotes disjoint union. The vector space of \(k\)-forms on \(M\) is denoted by \(\Omega^k(M)\).3

Typically, people denote \(\alpha(N)\) by \(\int_N \alpha\), and I will do that here. This is an alternative to the definition in most textbooks where we:

- describe dual-vectors

- tensors on vector spaces

- linear k-forms as anti-symmetrized tensors

- bundle it all on \(TM\)

- define \(k\)-forms as sections.

- attempt to define the integral of a \(k\)-form

- fail

- Refer to an appendix on partitions of unity (and pray nobody reads it)

You’re free to pick your poison, since these definitions are roughly equivalent.4

In any case, using our definition, we can define \(d \alpha := \alpha \circ \partial\). In other words

Definition: The exterior derivative is the pre-composition operation on \(\Omega^k\) by the boundary operator.

Stoke’s theorem is now a tautology.

It’s also intuitively clear that the boundary of the boundary is an empty set.5.Thus we see that \(d^2 \alpha = d(d\alpha) = d\alpha \circ \partial = \alpha \circ \partial^2 = 0\).

Poincare Lemma

Realizing that \(d^2 \alpha = 0\) for all \(\alpha\) raises the question, if \(d\omega = 0\), then does there exist an \(\alpha\) such that \(\omega = d \alpha\)? The definitive and unambiguous answer is “sort of”. At each point in the manifold there exists a neighborhood, \(U\) and a differential form \(\alpha\) over \(U\) such that \(\omega|_{U_{}} = d\alpha\).6

Discrete exterior calculus (DEC)

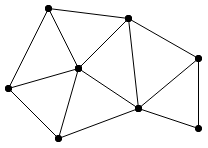

There is a discrete analog of this notion. We can discretize a manifold as a simplicial complex like this

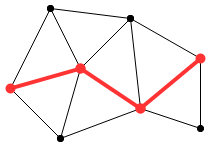

Then discretized functions are maps from the vertices to the reals. The discrete notion of a submanifold is a sub-complex, which looks like the high-lighted red part in this picture.

The definition of a discrete \(k\)-form (and a perhaps all of discrete exterior calculus) can be a obtained by using your favorite text editor (mine is VIM) and doing a find/replace to substitute the word “manifold” with “simplicial complex” and the word “sub manifold” with “sub complex”. By drawing arrows on edges we get oriented simplicies, and thus oriented simplicial complexes. We then obtain

Definition of discrete differential forms: A discrete \(k\)-form, \(\alpha\), over \(K\) is a map from oriented \(k\)-subcomplexes of \(K\) to the reals, such that \(\alpha(N_1 \uplus N_2) = \alpha(N_1) + \alpha(N_2)\), where \(\uplus\) denotes disjoint union.

Again, we will use the notation \(\int_N \alpha\) to denote \(\alpha(N)\). We denote the set of discrete \(k\)-forms on \(K\) by \(\Omega_d^k(K)\)

Discrete Stokes Theorem

In the discrete case, the Stokes theorem is not really a theorem but a definition. Let \(\partial K\) denote the boundary of a simplicial complex, \(K\). For a given \(\alpha \in \Omega^k_d(K)\), we say \(d\alpha\) is the unique \(k+1\)-form such that \begin{align} \int_{K} d\alpha = \int_{\partial K} \alpha \end{align} for arbitrary sub-complexes \(N\).

Discrete Poincare Lemma

Just as in the smooth case, \(\partial^2 = 0\) and therefore, we have that \(d^2 \alpha = 0\). We can again ask, if \(d \omega = 0\) for some \(\omega \in \Omega^k_d(K)\), then does there exists an \(\alpha\) such that \(d\alpha = \omega\)? Again, the answer is sort-of. At each vertex, \(x\), there exists a sub-complex \(U \subset K\) which contains \(x\), and a form \(\alpha\) on \(K\) such that \(\omega|_{U_{}} = d\alpha\).7

DEC for finance

We can represent the trade-network of the economy as a massive simplicial complex. The vertices represent commodities, and the edges represent trades.

At any given moment, apples might be trade for oranges at a rate of 1:2. Bitcoin might trade with respect to US dollars at a rate of 1:6,599.0. There are a lot of trades, and the most natural way to represent them all is using a discrete one-form, \(\alpha\). Take any directed edge (trade) in the network, and \(\alpha\) tells you the log-exchange rate between the two vertices (commodities).

Recall, the no arbitrage principle says that if we execute a circular sequence of trades, \(\gamma\), then the total result is no gain or loss. So \(\int_\gamma \alpha = 0\). Since the trade network is fully connected, \(\gamma\) can be seen as the boundary of a disk-shaped subcomplex \(D\), and we can use stokes theorem to write \(\int_D d\alpha = \int_\gamma \alpha = 0\). Now note that \(D\) is arbitrary (or arbitrary enough), so that we conclude \(d\alpha = 0\). This gives us yet another description of the no-arbitrage principle

The DEC no-arbitrage principle: Let \(\alpha \in \Omega^1(K)\) represent the contracts in an economy. In a no-arbitrage economy, \(d \alpha = 0\).

By a discrete analog of the poincare lemma this mean \(\alpha = d V\) for some function \(V\). What is this \(V\)? Is it even worth knowing?

\(V\) is for Value

Specifically, I think, \(V\), is \(\log\)-value. If \(dV = \alpha\), and \(\alpha(\bar{xy}) > 0\), then intuitively, \(y\) is more valuable than \(x\), and we find \(V(y) > V(x)\)8. However, \(V\) is only well defined up to a constant function. \(\tilde{V} = V+c\) also satisfies \(d\tilde{V} = \alpha\). This is because \(V\) is really the logarithm of value, and value itself is not an absolute quantity. I don’t believe that intrinsic value makes a lot of sense, because there is no such thing as a “value util”. People speak about value in concrete units like big macs9, or dollars (which are only valuable because you can exchange them for things like big macs). Because we really only define the relative value of things we should view value as a probability distribution over all the commodities. Probability distributions need only be defined up to a normalization constant, and so the log of a probability distribution need only be specified up to a constant. The function \(V\) has this very property, and thus my suspicion that the value of a commodity is given by \(P = \exp(V)\) (defined modulo an immaterial multiplier).

Arbitrage economy

How about when there is arbitrage? What can be said in such cases? We’ll firstly, if \(d \alpha \neq 0\), then there is no \(f\) such that \(df = \alpha\). In other words, there is no collectively agreed upon value for the commodities in an economy that has arbitrage opportunities.

That’s not quite the end. While we can’t find a price, there is something positive I can still say. We know that \(d(d\alpha) = 0\), does this translate to anything familiar?

Flux in in the economy

To make things familiar, let’s make things more elementary. In fact, lets make them pre-school. I think we should literally be playing with my sons toys to understand this. Don’t worry, he lets me take his toys. He just cries.

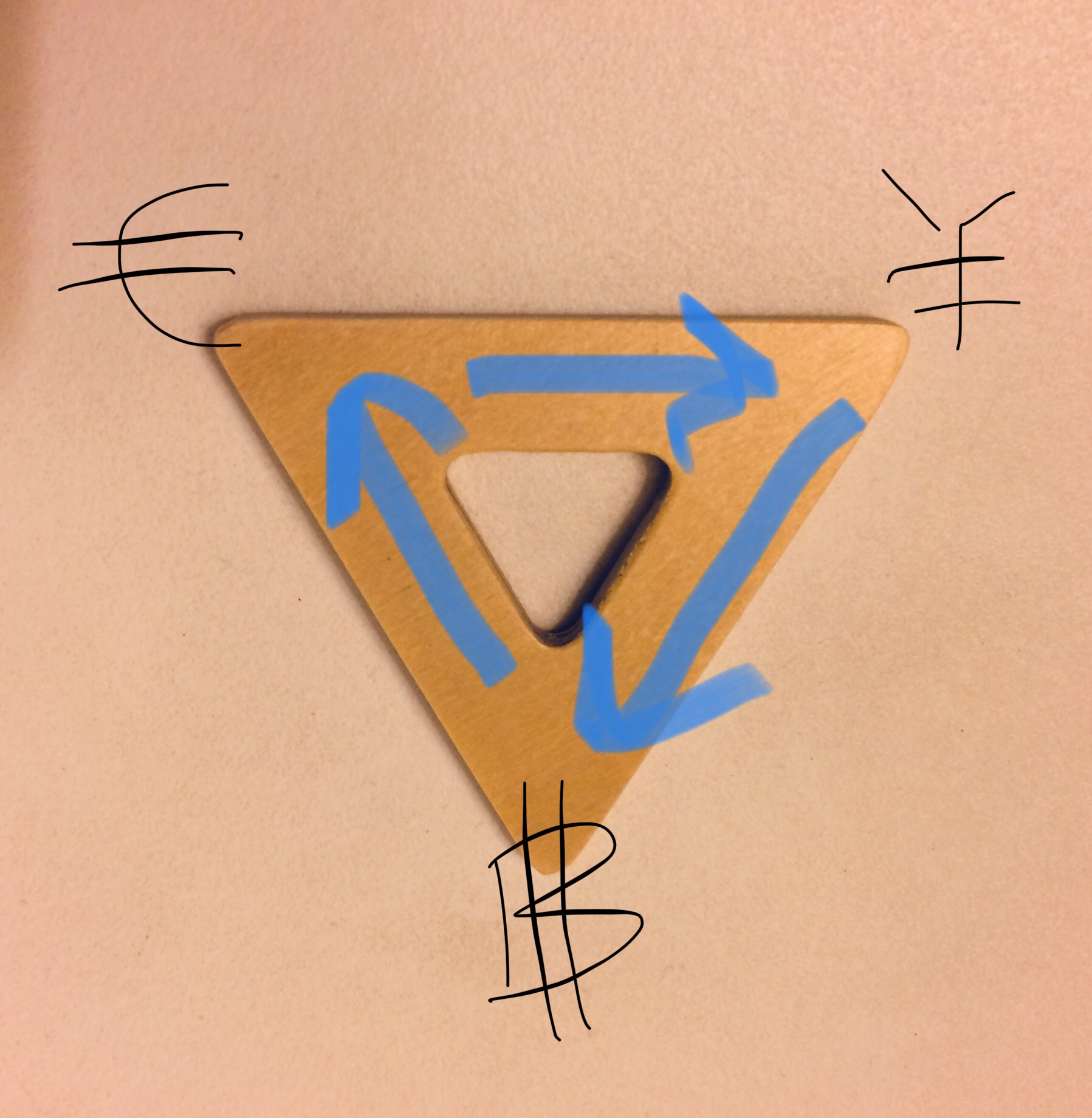

The minimal manifestation of an arbitrage opportunity requires three entities, let’s say they are currencies: Bitcoin, the Euro, and the Yuan. An arbitrage opportunity means executing a cycling sequence of trades as depicted below

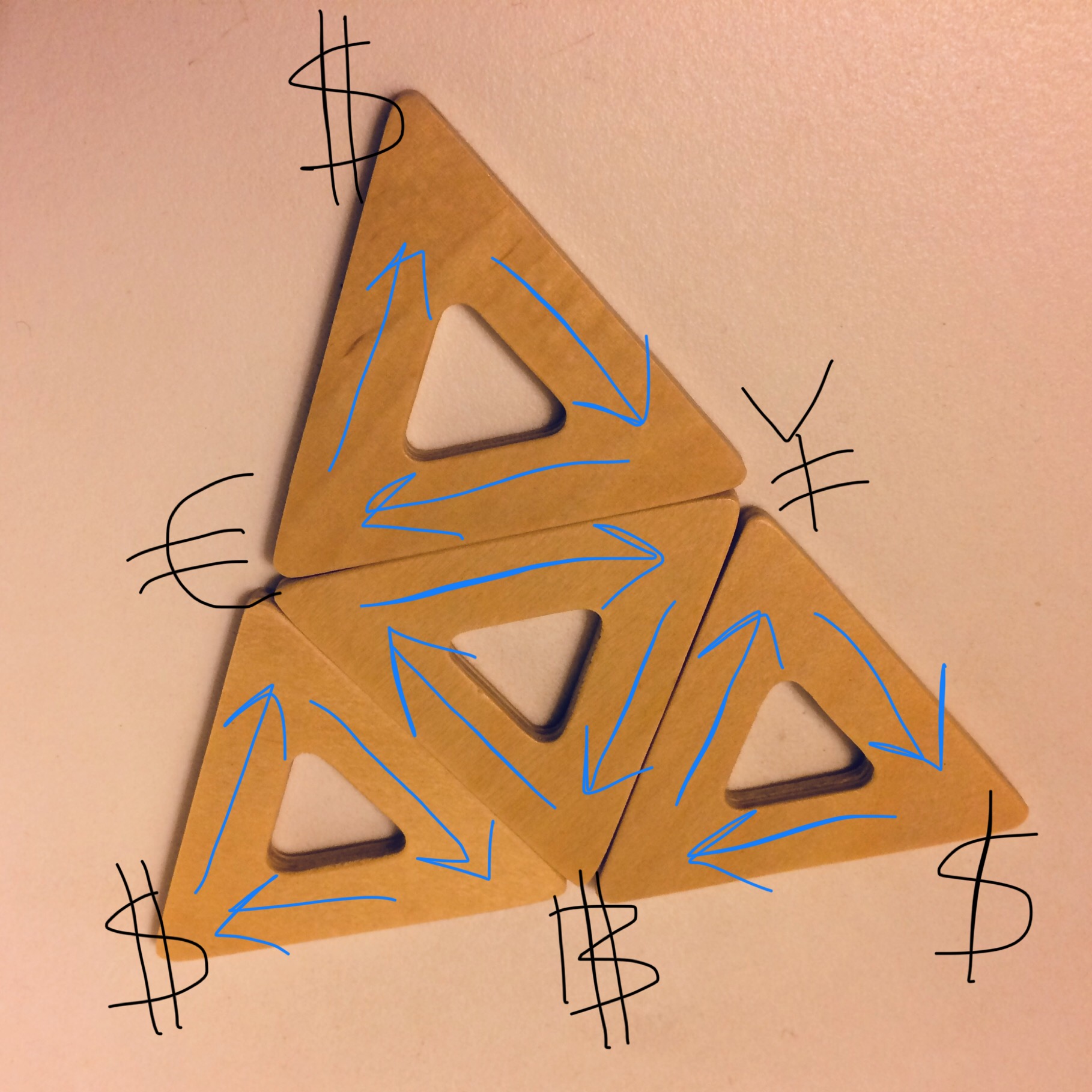

will result in a profit going clock-wise, and a loss if you execute the trades counter-clockwise. Don’t forget, that in any trade it takes two to tango. Each edge of the triangle is a trade with two sides, and thus another triangle. In particular, there are most likely three other individuals out there, executing there own trade cycles.

Perhaps these individuals reside in the US, and so all the trades are cycles that start and end in US dollars.

Let’s say \(\alpha\) is the one-form which represents the trades along the edges. Then \(\omega := d \alpha\) is a two-form, and it lives inside each of the triangles. In particular, \(\omega\) represents the profit/loss from traversing the cycles depicted above.

How do we think about \(d \omega\)? Recall, the last time we applied the exterior derivative, \(d\), we turned something that lived on edges (a discrete 1-form, \(\alpha\)) into something that lived on triangles (a discrete 2-form, \(\omega = d\alpha\)). So it seems natural to suspect that \(d\omega\) is something that lives on tetrahedron.

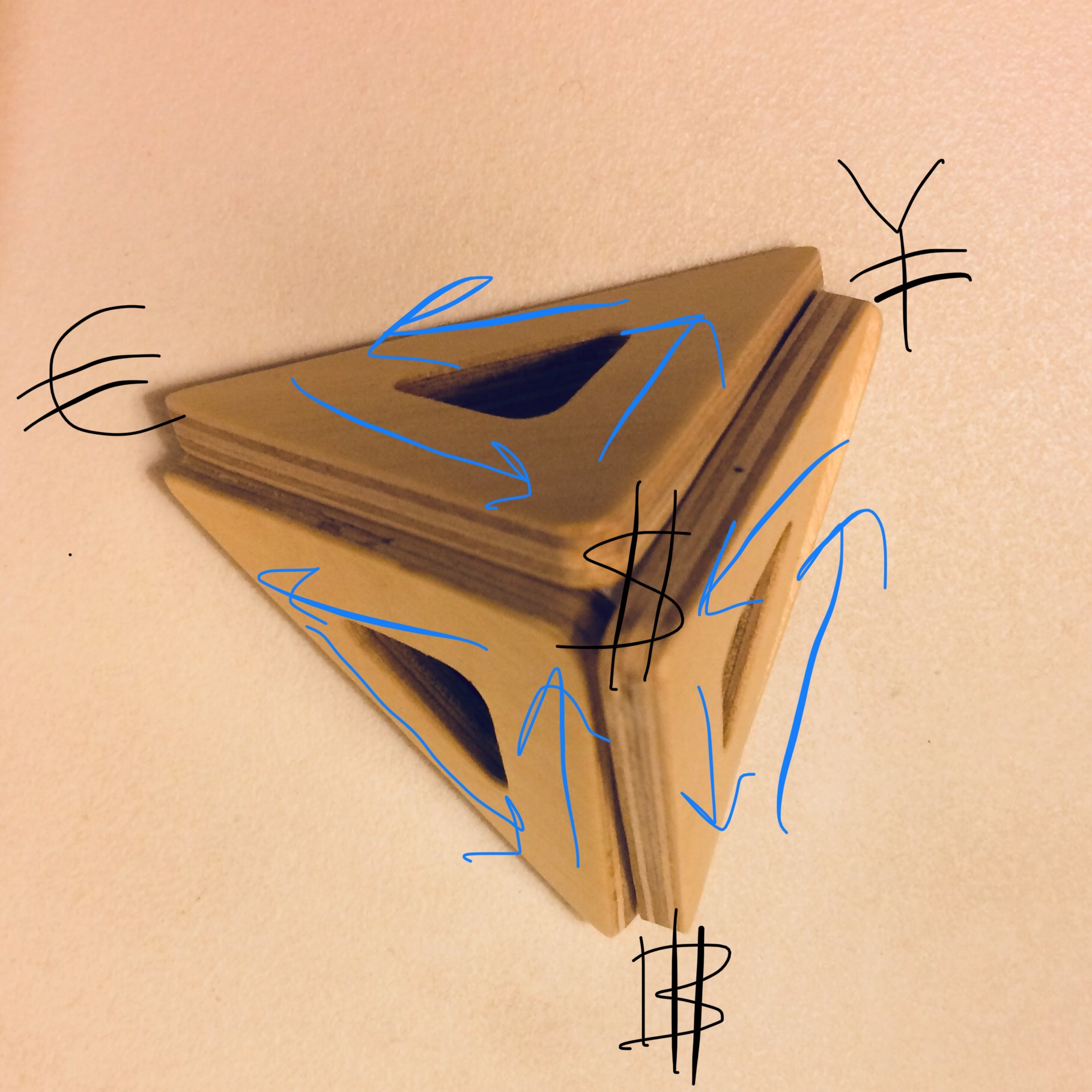

Note that US dollars appears 3 times in the last image (they are the outermost vertices). A graphical lie! These points should be identified with one another. That means we just fold those triangles so that the US-dollar vertices all meet, and the whole complex just becomes a tetrahedron (a.k.a. a 3-simplex).

The formula for \(d \omega = 0\) boils down to summing the profit/loss for each face and storing it inside this tetrahedron. That’s our 3-form in a nutshell. \(d \omega = 0\) is just DEC speak for the fact that trading is a zero sum game.

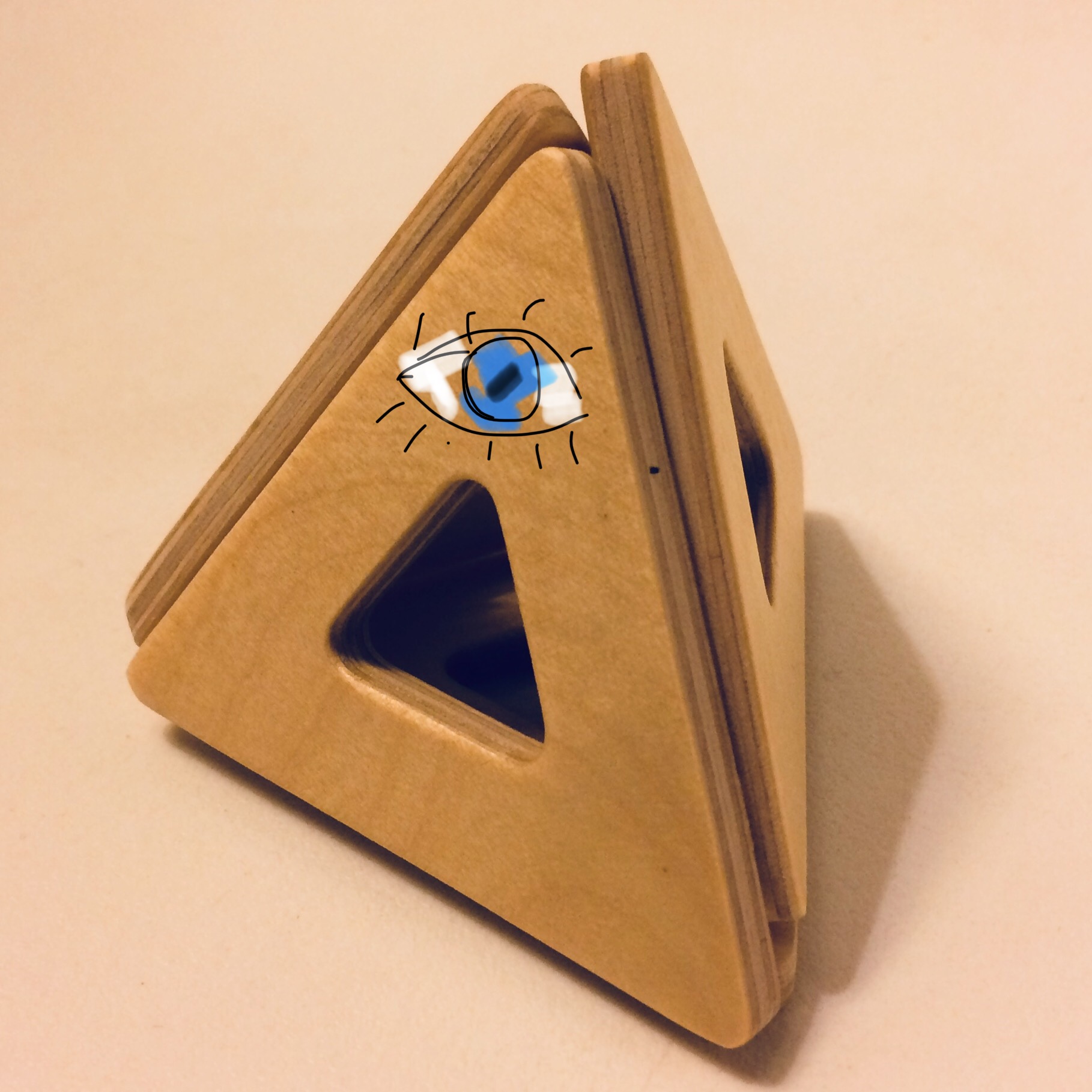

I’d like to show this tetrahedron from another perspective, just to make another point.

the conspiracy deepens… Okay, toddler is shouting at me, time to return his creepy blocks.

the conspiracy deepens… Okay, toddler is shouting at me, time to return his creepy blocks.

Gripes and under-developed musings

I’m like this formalism, but there are major issues

- Typically the economy is growing or shrinking. It’s not really zero-sum.

- Typically there are multiple contracts floating around for some trades, and zero contracts floating around for others.

Non-zero sum?

By construction, \(d^2 \alpha = 0\), and this equation jives with a zero-growth economy. However, the economy is typically not zero-growth. It’s almost always growing or shrinking. Moreover, the presence of two-forms for representing profits/loss tickles the physicist in me, and makes me think about fluxes and divergence. Perhaps the way to think about growing/shrinking economies is to think about breaking some no-divergence criterion. Not sure if this is the right track, and I’d rather just open the floor for discussion. If you’ve got an idea, I’d love to hear it. Jot it in the comments section.

Weighted networks and electronic trading

I think the links in the network should not be one-forms, but more like a distribution of one-forms. Prices are not fixed, and many quantitative theories of finance view them as random variables. I just complete a three part post where probability theory was given a category, and the morphisms were posteriors. Can that machinery be imported here?… Sort of… I think. I jotted some stuff down and found that Bayes theorem actually manifests as \(d\alpha = 0\). Thus, we end up in a no-arbitrage economy if we force our posteriors to follow Bayes theorem (which we should if we want to be self-consistent). Making money off this entails watching price fluctuations, and noting discrepancies between the contracts issued and the contracts you’d expect issued from your posteriors. My guess is that this is roughly what electronic trading at medium length time-scales involves.

Conclusion: the quest for monopoles

In this formalism I have been assuming the economy is fully connected. Geometrically speaking, this means the economy is a an \(n\)-dimensional simplex for some large \(n\). This is the simplest possible shape we could expect. However, trade barriers will remove some of the links in the network, and the resulting trade network might take on a more interesting shape, perhaps one with holes. Once you have a hole, the poincare lemma is only local. It is then possible to have an economy where \(d\alpha = 0\), but where there exists a loop \(\gamma\) that posses an arbitrage opportunity. Getting rid of such an arbitrage might be impossible due to topological obstructions (the trade barriers).

An analogous question arose in the physics community back in 1931, when Dirac wrote a quantum theory of magnetic charge. There is a geometric way of writing down Maxwell’s equations using (modest generalizations of) differential forms and one of the equations takes the form \(d\alpha = 0\). Dirac found that if there exists a magnetic monopole in the universe, then the charge of all particles would become quantized. Such a magnetic monopole would correspond to a hole of sorts, and the charge would manifest by integration of a differential form around this hole. To date, magnetic monopoles have eluded us, but the theory is consistent with reality (charge is quantized). To the best of our knowledge, magnetic monopoles are out there.

Finding an arbitrage is analogous (and mathematically identical) to finding a magnetic monopole somewhere in the universe.

Such a loop would make one person massively wealthy until the trade barriers are removed, and the market is able to clamp down on this exploit. Nonetheless, I’ve never heard of such a tactic.

I don’t imagine a Ready Player One type of global quest to search for such a thing.

However, virtually all transaction are of the form “[SOMETHING] in exchange for [A CURRENCY]”, and typically the currency is US dollars. You can’t form a loop if you only do trades of this form.

So perhaps there are holes in the network, fortunes just sitting under our noses, but we are blinded by our trust in the dollar.

Shoutouts

I always found DEC beautiful, and I think it’s an under-appreciated topic. If you’re a grad student looking for a topic, you could do worse than DEC. I learned about DEC and its applications from a lot of people, starting with my advisor Mathieu Desbrun at Caltech. I learned the foundations by studying Anil Hirani’s and Melvin Leok’s thesis, as well as numerous conversations with Melvin. In terms of applications, Keenan Crane is a heavy user of DEC and he has always impressed me. His ideas that are ostensibly for computer graphics, but I think anybody with enough creativity can see that they are useful elsewhere. On the more theoretical end, Ari Stern introduced me to idea of geometrically discretizing physics, and used DEC to discretize Maxwell’s equations. I also know Ari worked a bit with Eitan Grinspun who is another DEC user. There are a lot of other people in this community and I would encourage any curious young researcher to start traversing this network. The people I mention here are merely the ones whom were in proximity to me at the time (2010-ish), and it was the first community that came to my aide when my first advisor, Jerry Marsden (also a DEC geek), died in 2010.

Footnotes

-

See the Kutta-Joukowski theorem. ↩

-

Sometimes, one learns that a manifold is oriented if there exists a non-vanishing volume form on it (this is how I learned of it). However, you can define orientation prior to defining differential forms. A manifold is oriented if there exists an atlas where the transition maps are all orientation preserving (i.e the determinant of the Jacobian is positive). ↩

-

What’s missing in this definition is analysis. I’m not exactly sure how best to address this. My gut tells me that Peter Michor and his students know best. It’s somewhere in this book, either explicitly or implicitly. Perhaps it’s as simple as looking at the space of smooth embeddings, \(\operatorname{Emb}(S,M)\) as an infinite dimensional manifold. We’d say \(\alpha \in \Omega^k(M)\) is \(C^s\) if \(\alpha \circ f\) is a \(C^s\) endomorphism on \(\mathbb{R}\) for any \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \operatorname{Emb}(S,M)\) of class \(C^s\) and any \(k\)-manifold \(S\). ↩

-

Actually these definitions are not equivalent. The traditional definition is a special case of the more general definition given here, analogous to the relationship between measures on a manifold, and volume forms. However, when I learned differential forms, I found it really difficult to discern the motivation (which was integration, but that’s not until Chapter 10 or somthing crazy). Why not just introduce integration off the bat? ↩

-

Rigorously proving \(\partial^2 = \emptyset\) took me a bit of effort actually. I proved it in a brute force way. Let \(\mathbb{H}^n\) denote the half space of dimension \(n\). Consider an arbitrary chart on you manifold with boundary \(\{ \varphi_\alpha: M \to U_\alpha \cap \mathbb{H}^n \}\). Note that the sets \(\varphi_\alpha^{-1}( U_\alpha \cap \partial \mathbb{H})\) form an open cover of \(\partial M\), and \(\partial \mathbb{H}^n = \mathbb{R}^{n-1}\). Therefore \(V_\alpha := U_\alpha \cap \partial \mathbb{H}^n\) is just an open subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{n-1}\) for all \(\alpha\) and the maps \(\varphi_\alpha\) restricted to \(\varphi_\alpha^{-1}(V_\alpha)\) form a chart for \(\partial M\). This chart is apparently a chart for a manifold without boundary. QED. ↩

-

We generally can’t paste all these neighborhoods together to form a global \(\alpha\) over all of \(M\). The reason for this is typically an entry point to algebraic topology. ↩

-

Mathieu Desbrun, Melvin Leok, Jerrold Marsden, “Discrete Poincare Lemma”, Volume 53, Issues 2–4, (2205) ↩

-

possible sign errors here, but the idea holds. ↩

-

See the big mac index ↩